|

|

|

|

|

Out of the Mist of Lore

(The following story also appears on the baseball website baseballguru.com. It is about a remarkable man who had a remarkable career.)

By A.C. Haeffner

He was a little old man, bald and with an interesting face:

subtle age lines, gray mustache, pronounced bags under the eyes

... and a look in those eyes that bespoke world-weariness.

But as interesting as it was, it was also an obscure face --

at least there, on that day, when compared to all the famous

faces at hand.

I suppose it was that obscurity, that anonymity -- a byproduct of a career in which he played in the shadows -- that was keeping members of the press from approaching him. They were nearby -- mere yards away -- but paying him no heed, attending instead to more recognizable figures of baseball past and present.

This was the Hall of Fame induction weekend of 1987 -- my first such weekend, an experience for which I had prepared by obtaining credentials that got me close to the dais during Sunday's induction ceremony behind the Hall, and out on the diamond at Doubleday Field on the Monday afternoon of the annual Hall of Fame game. The credentials were obtained through a newspaper at which I worked, but I was not in Cooperstown to write any stories; I was there as a lifelong fan of the game.

Both days were gorgeous, I remember -- clear and with uncommonly bright sunlight. They were a perfect pair of days for celebrating our national pastime -- for enjoying the cadences of ceremonial pomp on the one hand, and the cadences of a ballgame on the other.

Reporters and photographers were taking advantage of the pleasant Monday weather, wandering about the Doubleday field, interviewing and taking pictures of members of the New York Yankees and Atlanta Braves -- combatants a half-hour later in the Hall of Fame game. The two teams had arrived by bus a short time earlier, and were now alternately doing calisthenics, playing catch and talking to the press.

There were other interviews going on, too -- with Hall of Famers who had taken in the annual induction ceremony the day before and stayed to watch the Monday contest. On the field near home plate were the likes of Ted Williams, Stan Musial, Robin Roberts, Lefty Gomez and two new Hall members: Jim "Catfish" Hunter and Billy Williams.

A third man had been enshrined on Sunday, as well, but was

attracting no such attention. It was he who had caught my eye:

the little old man with the interesting, but less-than-famous,

face.

His name was Ray Dandridge.

Unlike the other Hall members, Dandridge -- a long-forgotten hitting star and standout third baseman of the old Negro Leagues -- was seemingly of no importance to the press now that the ceremony enshrining him had passed. No photographers were taking his picture, and no reporters were asking him questions. He was standing alone in front of the Doubleday first-base dugout, his arms at his side and his face impassive, his eyes darting here and there across the green of the field, across the sea of activity.

At first I felt a little sorry for him. How must he feel, I thought, being inducted one day and overlooked the next? But practicality soon nudged sympathy aside.

Here was a perfect opportunity for me to meet one of the greats -- to actually have an exchange that might go beyond the shouted queries and rote answers taking place elsewhere on the field. So I sidled up to him and spoke his name.

"Mr. Dandridge."

"Ray" just didn't seem right. I could call Hunter "Cat" and Williams "Billy," but Dandridge at 73 years of age carried a mystique about him -- a dignity upon his bandy legs and behind his slow, wheezing pace.

He looked around, as if trying to locate the source of the words.

"Mr. Dandridge," I said again.

He found me to his right, turned and looked up. He listed at 5 feet, 7 inches, but age and gravity had taken him lower, making my 5-9 seem tall.

"Hmmmm?" he asked.

"I just wanted to say that I enjoyed your speech yesterday," I said.

He had given a rambling but heartfelt talk at the induction ceremony. Speeches were not his strong suit, but sincerity evidently was, and that had been appealing. That, and the joy he had exhibited.

"Hmmmm?" he said once again. "You did?" He paused, pursing his lips, before continuing in a slow, singsong fashion. "Well, I don't know why. I didn't do nothing but speak a few words. An awful lot of people said it was good, though … so I guess it must've been."

He looked out at the field again, thinking, then back up at me.

"What did you like about it?" he asked.

I hadn't expected that, and smiled.

"I like to see people who are happy," I said.

Ray Dandridge had been very happy on induction day, and rightfully so.

Consigned by baseball's color barrier to the Negro National League, the Mexican League and the Cuban Winter League throughout the 1930s and '40s, he had played late in his career in the American Association -- on a New York Giants farm club in Minneapolis -- hoping for the call to the big leagues after Jackie Robinson had smashed the barrier and Larry Doby, Satchel Paige and a teammate named Willie Mays had been promoted.

But the call never came, despite a level of play for Minneapolis that earned Dandridge league MVP honors in 1950. No, the call never came, and so he never got to play to the large crowds in major league ballparks -- never received the attention that his achievements should have earned.

Two decades and hundreds of games -- many lost in the mist of lore that shrouds Negro League ball -- finally eroded the talents of one of the best third basemen ever to play the game. He packed it in before the '50s had reached their midpoint -- after four seasons with Minneapolis and one final year in the Pacific Coast League. He later scouted briefly for the San Francisco Giants, worked as both a recreation center supervisor and a bartender in Newark, New Jersey, and retired in 1983.

He settled in Florida, enjoying the warmth and living the quiet life.

Then the Hall of Fame Veterans Committee got around to electing him -- 15 years after Dandridge had been listed as one of the top five Negro League performers for Hall consideration. In those 15 years, 10 of his Negro League contemporaries -- which means several who weren't on that first list -- had been inducted.

That had prompted Dandridge, in his induction speech, to say: "I just have one question: What took you so long?"

Now, standing near that dugout at Doubleday Field, he smiled in turn at my answer.

"Oh, my, yes," he said. "I'm happy. That's for sure. The Hall of Fame is a great honor."

He looked out at the field once again, in the direction of the third-base area, a realm he had known so well -- on so many diamonds -- so many years before.

"It's just that …" he said, and stopped. Several seconds passed, and I thought he was through talking.

Then he sighed. The words came out softly, and I wasn't sure -- still am not sure -- whether he was addressing me or gently mouthing a private thought.

"I just wish everyone could have seen me in my prime,"

he said. "I just wish … everyone could have seen me

play."

(Ray Dandridge died on February 12, 1994 in Palm Bay, Florida.)

|

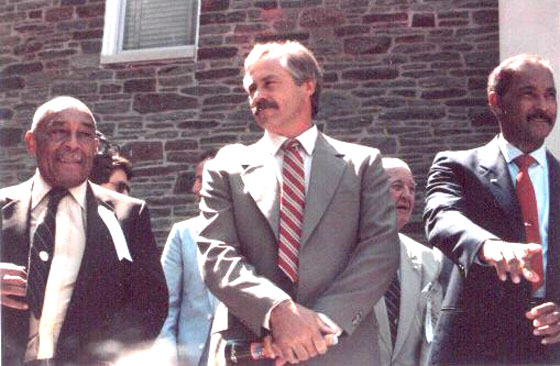

Photo above: From left, Ray Dandridge, Jim "Catfish" Hunter and Billy Williams at their induction ceremony behind the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, 1987. (Photo by A.C. Haeffner)

Some Other Creative Writing

We offer on the accompanying links some creative writing by local residents, the first by Bob Brown of Montour Falls: "The Wave." See Brown.

We also offer a look back at a political day in 2000 -- when Senate hopeful Rick Lazio stopped in Watkins Glen. It is written by publisher/editor Charlie Haeffner and titled "Of herbs and politicians." See Herbs.

And then there are the reminiscences of Betty Appleton, long of Australia, but before that an Odessa area resident who raised six children out near Steam Mill Road. See Appleton.

Charles Haeffner

P.O. Box 365

Odessa, New York 14869